The Irishman

If someone were to ask me – as an aged Frank Sheeran aka The Irishman asks a nurse towards the end of the film (and his life) – whether I knew who Jimmy Hoffa was, I’d have the same reaction as the nurse, who hasn’t a clue about the former President of the labour union The International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

I’m aware about the socio-political history of my own country (to some extent) but not of the West, and certainly not to the extent that I’d know about a union leader.

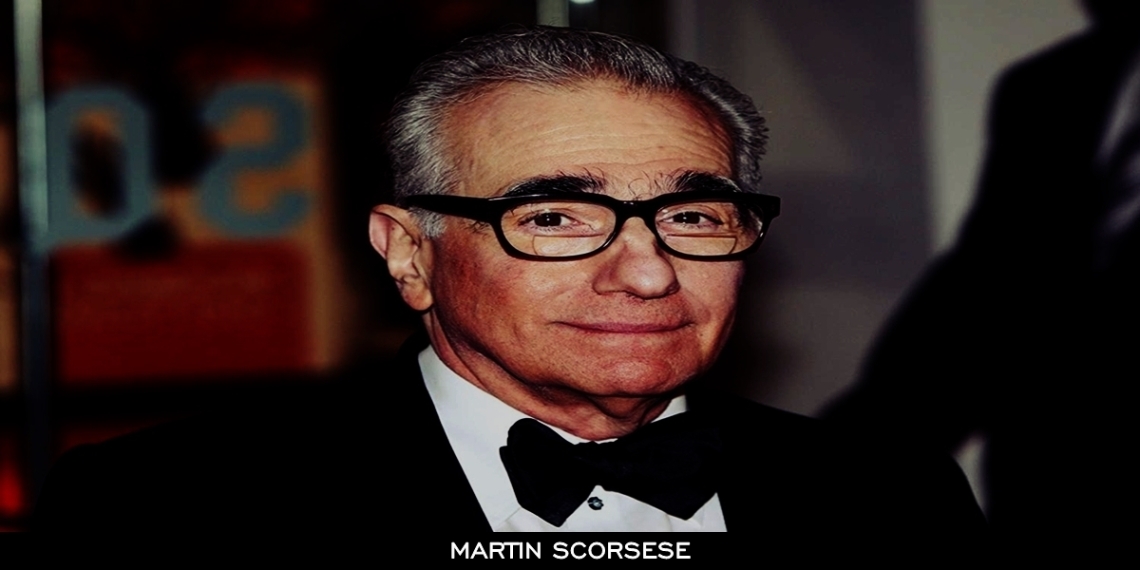

Martin Scorsese’s newest film The Irishman centres around the man who claims to have assassinated this Hoffa fellow. Frank Sheeran – a veteran of the Second World War – was a hitman for the Pennsylvania mob back in the day, and through Charles Brandt’s book I Heard You Paint Houses (upon which the film is based), claimed to have killed Hoffa, a longtime friend of his. Sheeran’s claims have been disputed, but in themselves make for juicy, film-worthy material.

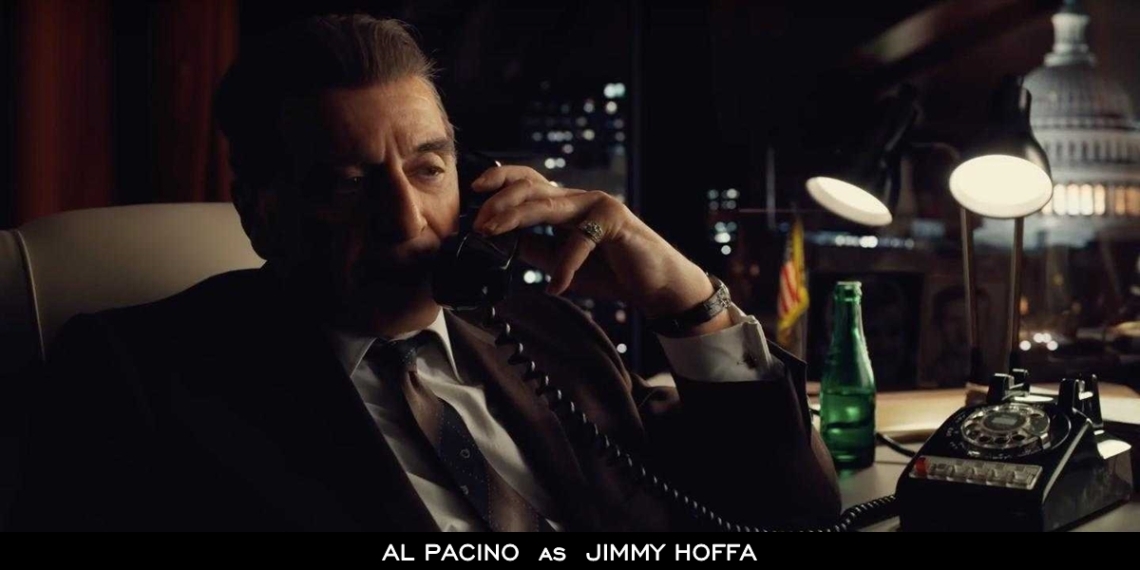

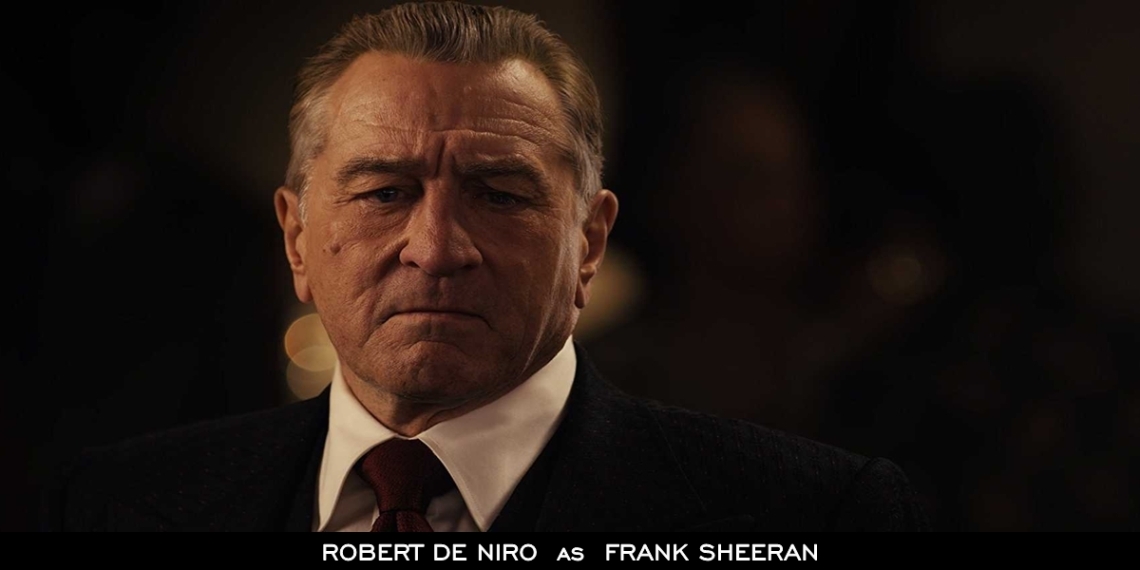

To play Sheeran, Scorsese teams up, after twenty-four years, with Robert DeNiro, having previously directed the actor in Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Casino, among other films. Playing Hoffa is another legend – Al Pacino, and the main cast is rounded off by Joe Pesci, who returns to acting after nine years as Russell Bufalino, a mob boss and Sheeran’s mentor.

All three actors are over seventy-five, but the strange thing is that Scorsese sticks with them playing their much-younger versions rather than recruit other, possibly lesser talented hands. Through extensive visual effects, DeNiro loses fifty years of his age, Pacino about twenty-five, and Pesci some ten-odd. It’s the biggest gamble one can imagine being taken in a film like this and, having been the oft-repeated cause behind the film’s ballooning budget, was a key marketing tool in Netflix’s arsenal to push the film.

The marketing may have worked, and thank heavens for that, because the effects don’t. While there can be no doubting the VFX team’s commitment and hardwork, it’s impossible to let slide the fact that De Niro doesn’t – at any point in the film – look younger than sixty. And there’s a scene in the film where he is twenty-five. The same applies to Pacino, who looks the age of the character only when Hoffa meets his end. Pesci survives the VFX issue because Bufalino was so much older than Sheeran to begin with. And it’s not just the effects – it boils down to DeNiro being as old as he is and having to move around as though he is much younger. It just doesn’t work.

But that’s the sole blemish on what is otherwise a pure cinematic experience. On a laptop, though.

Mind you, The Irishman is a rambling film. After all, the device it uses to convey this story of mobster America fifty years ago is a rambling old man (the make-up on De Niro makes it easy for one to believe he is on the other side of eighty). Old man Sheeran is narrating to us the trip that led to Hoffa’s disappearance, a trip he took with his wife, and his mentor and his wife. On one of their stops early in the trip, Sheeran points out a petrol pump (gas station to Americans) to Bufalino, who takes a while to remember that this is the place he met a much-younger Sheeran some twenty years ago, before he became a hitman. Which is how the story jumps back even more, to a strange-looking Sheeran driving a truck.

The Irishman is not a classic gangster film. There are no grotesque close-ups of the murders Sheeran commits. The violence is there, but it’s kinetic. Each spray of blood is calculated. I must confess here that having not watched any film about violent crime by Scorsese barring The Departed (which is a good film, but not a great one), I know not whether this measured depiction of violence is the man’s forte or not. What I do know is that it works big-time in The Irishman. By not drawing the audience’s attention to each of Sheeran’s acts of “painting houses”, Scorsese intends to convey how Sheeran normalised violence and murder and brutality. This is, at the end of the day, a film about Sheeran, and though the same point is driven home later in the film, it’s a sign of things to come.

It’s a film about the ramblings of an old man, who is not justifying his crimes or lionising what he did: it is what is. As simple as that.

Scorsese fills the cast with actors who are known but unknown. Of the supporting players, the only one who probably has recognition worldwide is Harvey Keitel, who plays Angelo Bruno in what is a bit part. Anna Paquin and Bobby Cannavale too get a raw deal, but make the most of it. The chunkier roles go to Ray Romano (Everybody Loves Raymond, The Big Sick) and Stephen Graham (Band of Brothers, Boardwalk Empire). Romano, as Bufalino’s cousin Bill and lawyer to every single one of the criminals on screen, is endearing. He doesn’t make a big deal of defending the bad guys. He is aware of everything yet unaware of it by how he keeps his distance from the happenings. Graham, in the most filmi role of the film, plays Tony Provenzano, a showy, larger-than-life Teamsters official. Graham owns the scenes he is in, chewing up the scenery without making proceedings annoying.

Joe Pesci returns to the screen after nine years in the wilderness. Pesci, whom I have known largely as Harry of the Harry-Marv Home Alone duo, is in good touch, playing the ageing patriarch of a mobster that Russell Bufalino was perfectly. He rarely raises his voice, preferring quiet instructions over bombastic orders. It’s a measured performance, and the stand-out act in the film.

Joe Pesci returns to the screen after nine years in the wilderness. Pesci, whom I have known largely as Harry of the Harry-Marv Home Alone duo, is in good touch, playing the ageing patriarch of a mobster that Russell Bufalino was perfectly. He rarely raises his voice, preferring quiet instructions over bombastic orders. It’s a measured performance, and the stand-out act in the film.

Al Pacino has a ball playing the loud, over-the-top Hoffa, enjoying his scenes with the same relish he shows while devouring sundaes. Hoffa is paranoid, power-hungry and every other despicable thing a politician should be, but Pacino also humanises him, mostly through his scenes with Sheeran but also in small portions through his bond with Sheeran’s daughter Peggy. Hoffa is cold-blooded in some ways but with a temper that shoots through the roof. Pacino, with his remarkable voice, makes it one of the more interesting performances of his in recent times.

Al Pacino has a ball playing the loud, over-the-top Hoffa, enjoying his scenes with the same relish he shows while devouring sundaes. Hoffa is paranoid, power-hungry and every other despicable thing a politician should be, but Pacino also humanises him, mostly through his scenes with Sheeran but also in small portions through his bond with Sheeran’s daughter Peggy. Hoffa is cold-blooded in some ways but with a temper that shoots through the roof. Pacino, with his remarkable voice, makes it one of the more interesting performances of his in recent times.

The visual effects may not have worked but Robert De Niro sure does. He gives Sheeran a lot of himself – the head movements, the twinkling eyes (which are a strange blue), the dead-eyed stares, while still making the character different. He is no ordinary hitman, Sheeran. He is a hitman without a conscience who doesn’t feel the need to bandy about his lack of remorse. He feels guilt, only not for his victims or their families but for how he treated his own kids. He is a conflicted man when the time comes to bump Hoffa off, but he can’t really turn down Bufalino. De Niro commands your presence with how understated a performance he delivers, keeping it subtle, never erupting for a moment.

The visual effects may not have worked but Robert De Niro sure does. He gives Sheeran a lot of himself – the head movements, the twinkling eyes (which are a strange blue), the dead-eyed stares, while still making the character different. He is no ordinary hitman, Sheeran. He is a hitman without a conscience who doesn’t feel the need to bandy about his lack of remorse. He feels guilt, only not for his victims or their families but for how he treated his own kids. He is a conflicted man when the time comes to bump Hoffa off, but he can’t really turn down Bufalino. De Niro commands your presence with how understated a performance he delivers, keeping it subtle, never erupting for a moment.

Aiding Scorsese in his attempt to tell this tale of bygone America are, among hundreds of others, director of photography Rodrigo Prieto and his longtime collaborator and friend Thelma Schoonmaker, who has edited the film. It’s thanks to Schoonmaker that the story within a story within a story heist is pulled off as well as it is. She makes the transition feel seamless. And despite the fact that the film runs to a length of over three hours, not for a minute does it get dull or boring. Something or the other is always happening. Prieto too does a wonderful job with the camera, giving the film colour that is in sync with the time periods the film depicts as well as moving the camera around wonderfully. The opening of the film, when the camera moves through the halls of the retirement home to find Sheeran, really stood out for how the camera moved – as though it were on a wheelchair.

Steven Zaillian’s screenplay is chatty. Very chatty. Make no mistake, The Irishman is a dialogue-heavy film, but because of the way it’s designed – it’s basically a memoir – none of it is a hindrance. Zaillian also somehow manages to make the entire political scenario a part of the film without complicating it or dumbing it down. It is what it is. He works the inter-personal relationships that form the crux of the film in beautifully – Bufalino and Sheeran are like father and son, Hoffa and Sheeran are brothers. Even the smaller characters – Mrs. Bufalino, for one – have some amount of depth to their interaction with the principal characters.

One can almost sense that this is the last time the Italian-American from Little Italy, NYC will venture near gangster movies. The Irishman is Martin Scorsese’s testament to the genre of films that brought him the fame and appreciation he commands today. It is no longer about the crimes or the motives or the payoffs. It is about the people who lead these lives. With this film, Scorsese takes a closer look at the man behind the weapon. That’s probably why the violence on screen is shot most from a distance, when going closer would’ve benefited the film in that it would’ve concealed the fact that De Niro is nearly seventy-five and that people – some people – thrive on on-screen violence.

One can almost sense that this is the last time the Italian-American from Little Italy, NYC will venture near gangster movies. The Irishman is Martin Scorsese’s testament to the genre of films that brought him the fame and appreciation he commands today. It is no longer about the crimes or the motives or the payoffs. It is about the people who lead these lives. With this film, Scorsese takes a closer look at the man behind the weapon. That’s probably why the violence on screen is shot most from a distance, when going closer would’ve benefited the film in that it would’ve concealed the fact that De Niro is nearly seventy-five and that people – some people – thrive on on-screen violence.

Scorsese confronts many things in the film, chief among them mortality. Nearing eighty, it wouldn’t be unkind to say that Scorsese is in the winter of his life. Perhaps that is what prompted the examination of life in general. That he happened to lock in on Frank Sheeran’s could just as well be a coincidence. Through this film, Scorsese examines the the work one has done in their life, the good and the bad. I don’t know about what Sheeran thought of his life’s work but Scorsese can be proud. Few would’ve tackled a subject like this in Hollywood, and his doing so proves that you can cast as many stars as you want and still be the man whose name is stamped across the film.

The Irishman is actually the perfect Netflix film. It will do different things for different people. If you don’t mind a three-hour-long film that doesn’t seek to entertain as much as it seeks to show an introspection on both the part of its characters and its director, it’s the film for you.

1 Comment