Greyhound

It’s unfortunate that Tom Hanks is seen as the perennial good guy by the public at large. Not unfortunate in the sense that he shouldn’t be a nice human being, unfortunate because it makes people overlook just how good an actor he is.

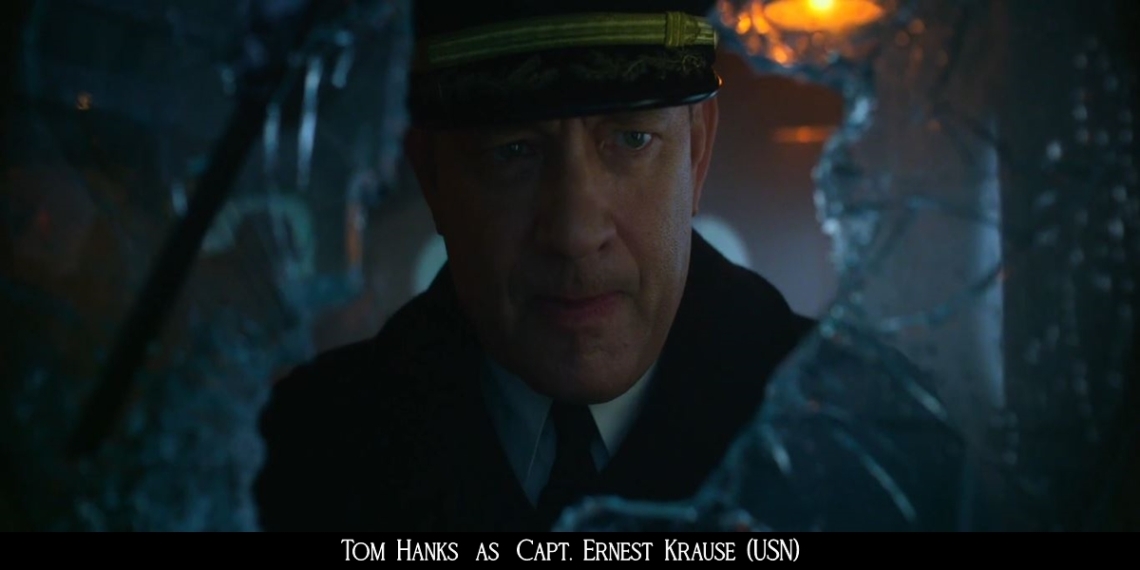

In Aaron Schneider’s Greyhound, which Hanks himself adapted from C.S. Forester’s novel The Good Shepherd, the actor plays USN Captain Ernest Krause, skipper of the titular destroyer which is escorting a convoy across the pond mere weeks after the United States has entered the Second World War.

It’s a typical Hanks role. Krause is a good man, a kind man, one who wants to get the job done with minimal damage. He is a father to his men (Hanks literally is so to one of the cast – his son Chet plays one of the many crew members). A trusted friend to his XO. If you look at the Hollywood directory, it’s crystal clear that nobody else could have played the part, or at least not the way Hanks does.

Greyhound is a tightly-wound film, one that wastes almost no time in cutting to the chase the German U-Boats are giving the Allied convoys. Like other war films recently (Dunkirk, 1917), Greyhound also keeps its viewers dead centre with the crew of the destroyer. And because the focal point of the film is Krause, our understanding of the crew also comes from him.

If you’re going to go into Greyhound expecting something like Das Boot, you’re going to be disappointed. It’s not so much a film about the destroyer’s crew as it is about a particular mission they are on. I say that because unfortunately, films like these end up getting lumped together. The account of a destroyer escorting a convoy will be as different from the shenanigans of a U-Boat crew as the exploits of a tank crew in North Africa will differ from those of an infantry unit heading into Burma.

Greyhound isn’t a perfect film by any means – the girlfriend subplot featuring Elisabeth Shue feels extraneous to the film’s otherwise precise narrative, the visual effects are shoddy (it isn’t practical to shoot the film at sea, of course, but even so, it clearly could’ve done with better effects), the looming threat of the U-Boat Wolfpack is underscored by the strangest sound design, perhaps to highlight how other-worldly Vizeadmiral (later Großadmiral) Karl Dönitz’s men were. The impression the sound is supposed to create is fear; it ends up sounding like something out of a sci-fi film and is terribly distracting.

The film’s largest strength is its leading man. Hanks knows what to do in this role. More importantly, he knows what not to do. His performance is one of economy, just like the film itself. He portrays the humanity of the ageing officer with finesse. It is one of those performances where a good actor is happy with just being, and Hanks does just that. He locates the conflict of the character and hits his marks consistently, helping tide over some of the film’s flaws.

Aaron Schneider makes some questionable decisions in the director’s chair, chiefly the way he uses the score and the way he stages some of the scenes, but he puts Hanks’ screenplay to good use, which is why the film doesn’t feel half-hearted. The other characters are defined by their interactions with Krause, and Schneider does well to document those interactions, especially the rapport between Krause and his XO (played by the wonderful Stephen Graham). Using throwaway lines and a different camera setup from the one employed in other sequences featuring crew members, Schneider conveys the friendship between the two men. He uses the destroyer’s black cook similarly, a man with whom Krause’s relationship is naturally one of a superior officer and a subordinate, but one with some layers to it.

It doesn’t hurt that the supporting players are all capable actors on whom Schneider can rely upon to put forth their feelings about their veteran-yet-greenhorn skipper.

The way the action at sea is staged stands out. Schneider and cinematographer Shelly Johnson bring the chaos of war to your bedroom (or drawing room, or bathroom, wherever the hell you watch the movie). Stripping the glamour of war is something pretty much every filmmaker today knows, having probably taken a leaf out of the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan, but what Greyhound strives to do better than most of its compatriots is allow the tussle to play out the way it would and put the viewer by Hanks’ side. We see ships being sunk, depth charges being fired, torpedoes being dodged – all fairly standard by the rules of the war-at-sea film – the difference is that there aren’t any glamourous shots of the situation. It’s chaotic, messy. Unlike the ground, where a lot more depends upon the man with the Lee Enfield, or the air, where the pilot of the Spitfire determines the course of action for a vast majority of his sortie, the ocean waves allow no one else to even flirt with the possibility of authority.

But what I truly liked about the film was how it chose to involve the viewer in the action on the bridge of the destroyer. The relaying of orders, the coming and going of the crew, these might all seem banal when there is a Wolfpack to evade, but Schneider makes it cinematic. He makes you invest in the crew as a whole, and how they operate like a well-oiled machine.

It’s the finer details that make up for Greyhound’s faults, and of course, Tom Hanks.

Varry axcallant

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike