Sardar Udham

People are, at their very core, hungry beings. Most of them crave something specific in life. It’s what our teachers in school called “ambition”. Some wanted to be doctors, some teachers, a few wanted to join the Services. Over time, the word “ambition” loses favour to “career”. For a few, however, a career is a luxury. They still hark for that which they were ambitious about.

For close to twenty-one years, a Kamboj orphan from Amritsar pursued an ambition. One that would earn him a place on the pantheon of modern Indian heroes. In her book The Patient Assassin, writer Anita Anand described him thus: ‘…For two decades he had worked at becoming the man who could make Sir Michael pay for Jallianwala Bagh, however, in the process, he believed he had become so much more…He would avenge the dead. He would inspire the living.’

1931: a momentous year for the cause of Indian Independence. Udham Singh, in prison for the last four years, is set free even as the countryside around him, once teeming with Ghadrites and HSRA revolutionaries, comes under scrutiny. Even as the British make good on a promise to ensure compliance with the Raj in “the Punjab”, a man who will strike at the heart of the Empire not only evades the cops on his coattails but makes for the mountains to the North-West, inducting into the USSR through Afghanistan.

It’s an admittedly unusual opening for a biopic, especially one made in the mainstream of Hindi cinema. They have beats that are all too familiar, narratives set in stone, with songs and drama sprinkled liberally. Sardar Udham does a complete left turn on that. Not only do we not see Udham – or Sher Singh, as he was christened by his parents – at birth, the entire structure of the film is such that it ends at the beginning.

For director Shoojit Sircar, no stranger to narratives hitherto unexplored, this is the ideal challenge: how do you make a film about a man whose passivity was the most remarkable thing about him, whose patience was other-worldly? The solution that Sircar comes up with injects little shots of life into the film rather than turn it into an adrenaline junkie of a production.

Sircar and cinematographer Avik Mukhopadhyay [October, Pink] conjure up images that haunt you. Much of the film is cloaked in mist, mirroring its subject’s life in the shadows. The normally-vivid Punjab countryside too gets this treatment: Udham, upon his release from prison, breaks through the fog around a cousin’s home; he and his friend Bhagat Singh (Amol Parashar in one of his lesser performances) meet with their revolutionary comrades in the early hours of the morn, riding bicycles through the swirling white. Magically, Sircar and Mukhopadhyay wipe the lens clean for the bigger moments, the pals which have no ambiguity. The colours remain muted for all but one part of the film: the Jallianwala Bagh massacre changes the visual language of the film in much the way it changed the social, political and historical landscape of India. The London scenes evoke the dreariness of Jean-Pierre Melville’s L’Armee des Ombres [shot by Pierre Lhomme and Walter Wottitz] and Tomas Alfredson’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy [shot by Hoyte van Hoytema], and how fitting is that – Udham is as much a spy as he is a resistor of an occupational power. My favourite shot, though, and I must highlight it, is just after Udham arrives in London. Local Indian Independence sympathisers (played by co-writer Ritesh Shah and casting director Jogi, among others) warn him about the possibility of MI5 – Britain’s internal intelligence service – and Scotland Yard having kept their eyes peeled for him. Almost as if to illustrate the point, the moment Udham is out on the street, he is, for the briefest of moments, spot-lit by a streetlight. It’s probably the showiest moment in the film, yet executed with silken skill such that you’ll only notice it if you look out for such moments.

The film is almost equally the story of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the civil authority behind Jallianwala Bagh and the atrocities in the Punjab. Splendidly played by Shaun Scott, O’Dwyer embodies exactly the kind of man that made the Raj tick, men to whom the slaughter of thousands was the “preservation of peace”, nothing more than the kind of bureaucrat that would form the cog of the Nazi war machine years down the line. He is a tad bombastic in his assessment of India two decades since his time there ended, and is boastful of his record in the Punjab, blissfully unaware that moments later, a Punjabi will put an end to the grisly chapter of 1919. O’Dwyer and Udham were more alike than either man would’ve liked to admit – they came from agrarian regions in areas under foreign rule, and were raised in less-than-privileged surroundings. The two were undoubtedly hard-working individuals, and each had a dogged determination about him to achieve his aims. Perhaps, had it not been for his pro-British upbringing, it might just as easily have been a young Michael O’Dwyer alongside Michael Collins in the Irish War of Independence. Sircar stages a handful of meetings between the two. The film even suggests that Udham was in O’Dwyer’s employ for a while and though the jury of historians is still out on whether that was the case, it allows Sircar to mine some tense moments.

There are pointed details to the design of the film, and Sircar isn’t keen on letting there be any room for interpretation. Sircar is particularly interested in the oneness of India as espoused by Udham who, when detained after shooting O’Dwyer, used the name “Ram Muhammed Singh Azad”, and in the Marxist-Leninist rhetoric of the HSRA, long brushed under the carpet by those who admire Bhagat Singh and Co. but disagree with their politics. Somewhere, Sircar seems to be saying, ‘Look, you might not like his politics, but you can’t wish away their existence. To do so would reduce Bhagat to a gunman.’ It’s odd then that Sircar should choose to depict the man, at the time of his execution, with a juda, the knot into which Sikh men tie their hair. An avowed and unwavering atheist, Bhagat had shorn his hair and beard at the time of his escape from Lahore in 1928 and never grew it back. It’s an appalling, nasty bit of revisionism, and looks worse when you realise that the authorities – political and religious – have long been fashioning Bhagat into a Sikh hero, and that Sircar’s misstep only stands to bolster their contention.

The film’s most fatal flaw is that in its disjointed narrative, it fails to make note of some key moments in Udham’s life that are very telling of his character: his service in the First World War in his mid-teens, and his American sojourn in the Twenties, during which he met and married a Latin American woman whom he subsequently abandoned. Sircar is keen to avoid the thorny side of Udham, choosing to let go of his maverick attitude and almost conman-like character since those aren’t attributes populists like attributed to freedom fighters. There’s also the insertion of Banita Sandhu’s character – a mute girl by the name of Reshma who 20-year-old Udham loves and who dies at the Bagh. Whilst obviously not treading too close to insinuating that she was one of the driving factors of his quest, it doesn’t at all seem far-fetched that the intention was very much to bring the viewer round to that idea.

These slip-ups wouldn’t be noticeable were Sardar Udham just another Bollywood biopic, another by-the-beats film that had more on its mind than the story it wanted to tell. The fact that the film is far superior to anything the Hindi film industry has produced in the genre in recent times, or ever, works to its detriment in this case: the sore thumbs really stick out.

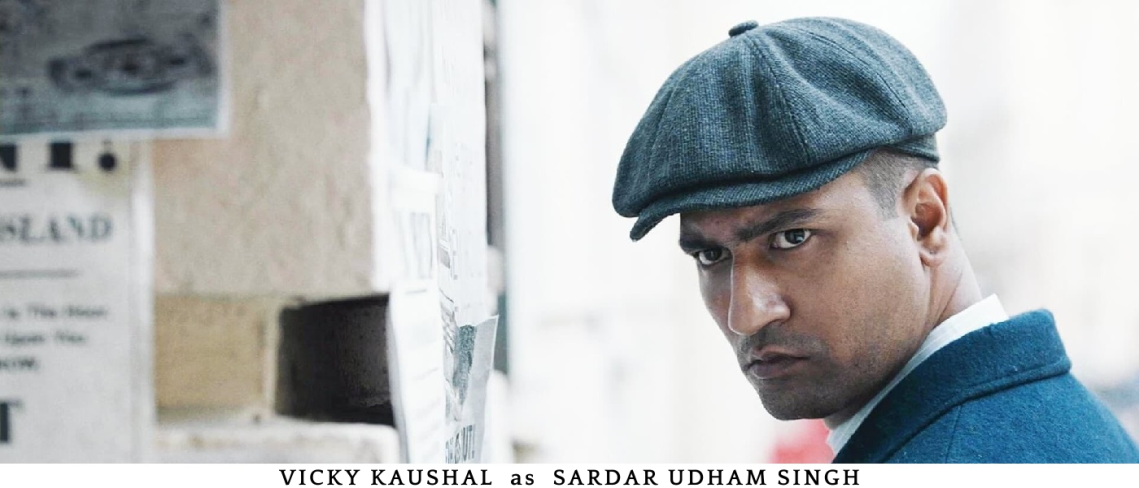

Sircar is lucky to have an actor of the calibre of Vicky Kaushal (Manmarziyaan, Raazi), for he tides over the film’s rougher patches with a sublime performance. Kaushal’s everyman quality is utilised to its fullest by his director. There’s a line in Fincher’s Mank, a film I love, that stayed with me: You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression of one. Kaushal does exactly that. He’s had films where he’s front-and-centre (Uri, for instance), but those have hardly allowed him to flex his skills as an actor at the level that Sardar Udham does. He is a quiet presence through the film, propelled by the narrative, thrust into action when he isn’t ready. He has the measure of Udham, with his rudimentary English and country-boy mannerisms (he is fond of laddoos, we are told), but doesn’t let that lapse into an imitation of a man out of place in the Western world. Kaushal slips into Udham’s skin, so much so that one forgets he is Kaushal: the evolution of the character, from a man who flinches while practising firing at a makeshift range to an emboldened assassin who confidently empties his revolver into his target, is felt through Kaushal’s shudders and blinks, and later as his dodgy gait turns into an upright, brisk walk which falls short of a swagger. On the occasions that Udham fails, he is overwhelmed by emotion at O’Dwyer’s lack of repentance, and undone by a momentary lapse of awareness at a rabbit shoot, and it’s Kaushal’s grimaces through which we feel the man’s grief. To counter that grief, he drinks. An unusual act for a freedom fighter, at least where popular discourse is concerned, but neither Kaushal nor Sircar care – to them, Udham is a young man with a burden, to lighten which he must drink. It’s a performance where the viewer feels truly immersed, despite the film’s missteps.

A word here for editor Chandrashekhar Prajapati (Madras Café, Bareilly Ki Barfi), who turns Sircar’s vision of a disjointed narrative into a cohesive whole where it matters not that an earlier fragment of Udham’s life has not been shown yet. The placement of the beginning at the end is the film’s deftest trick, and Prajapati makes it seem only natural.

Writers Ritesh Shah (Airlift, Chef) and Shubhendu Bhattacharya (Madras Café) make sense of Udham’s life through vignettes: their screenplay works the way cutscenes in video games do – adding context to the situation and letting it play out, with Sircar gently pulling the strings from time to time. That the scenes – barring the ones featuring Bhagat Singh – feature the detailing they do is an immense credit to Shah and Bhattacharya; it’s in the throwaway lines, in the snatches of dialogue, in the background as much as in the foreground, that Sardar Udham holds up. A hurdle the writing fails to leap over, though, is the twenty-one-year journey: at no point in the film does it seem like Udham has bided his time for that long. Kaushal simmers, he burns, but neither the writers nor Sircar create a sense of time, lapsing into the laziness of getting away with flashing the year on the screen.

It’s the big moments that naturally power Sardar Udham, but some of the finer details that Sircar pays attention to are worthy of mention: as he helps people out on the night of 13th April 1919, Udham ferries bodies and the injured on carts back up the very alley down which Dyer and his troops marched – there is a strange irony to the moment, and later still, when he realises that a toddler whose parents he’s trying to locate has been orphaned, it is the younger child who comforts the 20-year-old. It’s a heartbreaking moment Sircar stages movingly. Earlier in the film, the day before the assassination, we see Udham, who has taken a job as a cleaner at the venue, scrub the floors vigorously. As the scene unfolded, I recalled a brief glimpse we are given of Udham doing seva at a gurudwara in London. There is, even in the moments leading up to the event that’ll make him a hero, an almost religious fervour he displays. At that moment, in cleaning that floor, Udham shines upon the viewer the “holy” nature of his mission.

Sardar Udham leaves you pondering over many questions we need to ask ourselves about our freedom fighters and the role they have to play in modern India. Fittingly, it gives us no answers. As with Udham, we too will have to struggle our way to realising our ideals in an India that, unlike his, is our own.

1 Comment