Dune

Dune, for all its epic scale, is a very intimate tale – the story of a defeated, somewhat vengeful son who must navigate a complex world while coming to terms with his fate and dealing with his relationship with his mother. Scratch that, actually, because Dune is basically designed as an extended, two-and-a-half-hour prologue to the actual story. None of what I’ve mentioned is actually in the film: it’s what we, the audience, hope the second will deliver.

What exactly does Dune, bearing the title Dune: Part One, do? It sets up the entire story. Much like Baahubali: The Beginning, only that film ended on a “What the fuck?!” moment rather than the “Okay, what happens next?” curiosity that Dune leaves the viewer with.

I took my time thinking about Dune, for the film, on a scale and production level, almost overwhelms you. There is so much to admire, and just as much to unpack and understand. Film, whichever way you look at it, is transmission. Of information. Of ideas. Of knowledge. So much of cinema is about how you tell it, but a lot of it is also how you get that which is unfilmable across to the audience. Some films are weighed down by the text they display to frame the events of the film better – it’s a tedious, often boring manner in which to begin the film, even with the innovative twist George Lucas gave it close to fifty years back. Christopher Nolan (The Dark Knight, Dunkirk), for instance, loves walk-and-talk: characters communicate vital information about the film to the audience through a conversation they have. He’s done it particularly well in Inception, with actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Elliot Page walking the streets of Paris, and he has also done it terribly – in last year’s Tenet, where you cannot hear a word of the many John David Washington and Robert Pattinson exchange, which isn’t necessarily the worst thing given the film is too much of a bother to try understanding beyond a point.

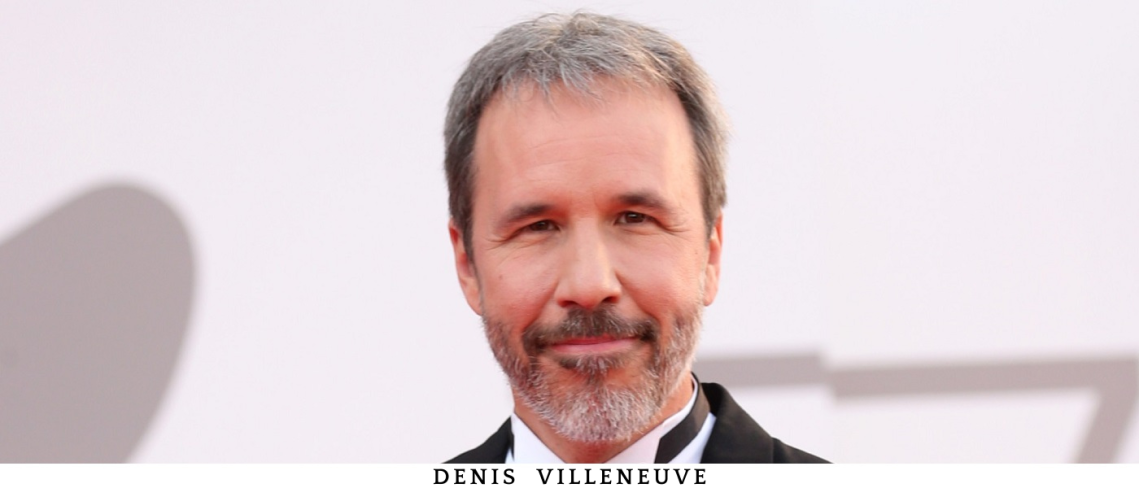

Exposition is vital to Dune as well, more so because it’s an adaptation of a literary behemoth. Denis Villeneuve had the unenviable task of translating what was put down on the page by Frank Herbert many decades ago and presenting it coherently to the audience, and especially to those such as me, who haven’t read the book. What Villeneuve does is actually quite brilliant. We the audience are only as aware of the stakes of the game as the film’s protagonist Paul Atreides, played by Timotheé Chalamet (Lady Bird, Little Women). Paul is a media buff, and most of his knowledge about the faraway land his family legion, known as the House Atreides, is ordered to assume charge of comes from films and what one can assume are podcasts. Even the traditional voiceover pieces are well-handled: first through a brief description of the occupation of the planet Arrakis by the House Harkonnen, acting on orders from the Padishah, and the few other moments where Chani – “played” by Zendaya (The Greatest Showman, Malcolm & Marie) – narrate bits and pieces of information play out properly for the characters of the film.

Exposition is vital to Dune as well, more so because it’s an adaptation of a literary behemoth. Denis Villeneuve had the unenviable task of translating what was put down on the page by Frank Herbert many decades ago and presenting it coherently to the audience, and especially to those such as me, who haven’t read the book. What Villeneuve does is actually quite brilliant. We the audience are only as aware of the stakes of the game as the film’s protagonist Paul Atreides, played by Timotheé Chalamet (Lady Bird, Little Women). Paul is a media buff, and most of his knowledge about the faraway land his family legion, known as the House Atreides, is ordered to assume charge of comes from films and what one can assume are podcasts. Even the traditional voiceover pieces are well-handled: first through a brief description of the occupation of the planet Arrakis by the House Harkonnen, acting on orders from the Padishah, and the few other moments where Chani – “played” by Zendaya (The Greatest Showman, Malcolm & Marie) – narrate bits and pieces of information play out properly for the characters of the film.

Villeneuve is at his most comfortable establishing his – or Herbert’s – world, and the nods to the past century of human existence and violence are pointed, particularly the hues of imperialism the film bears. The Padishah emperor orders the Leto of the House Atreides to assume charge of the planet Arrakis from a partner House – Harkonnen, even as Leto’s son Paul has strange visions of a future in which he partners up with Arrakis’ native tribe the Fremen in leading a jihad against the colonisers.

The influence of the Arab world is unmissable – the use of jihad is my own, but that’s a fair assessment of what Paul sees his future self carry out. When the women disembark the spaceship upon their arrival in Arrakis, one notices the hijab-esque scarves they are cloaked in. Later still, the Fremen are established as a sort of Bedouin outfit, which would make Paul some kind of Lawrence of Arabia, I suppose. The “spice” to protect which the Atreides are on Arrakis is a euphemism for oil. All these nods seem to point toward an anti-imperialist stance, only for Villeneuve to present us with the Atreides themselves, who have not a hint of grey about them despite serving a power whose business is colonisation. It speaks more of how little our world has changed that Herbert’s imagination – fuelled by the British Empire’s past – almost perfectly fits the neo-imperialist actions we have seen the United States undertake in the last couple of decades.

For such a complex, complicated setup, stale writing and unbaked characters are its biggest enemies. There are flashes of brilliance: the dread Villeneuve creates in the scene between Charlotte Rampling (45 Years, The Duchess) and Chalamet right at the start (it might remind a fair few of you of Se7en), the scene where Paul and Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson – Doctor Sleep, Mission Impossible: Fallout) overpower their Harkonnen captors after the film’s conflict-creation point, and when Jason Momoa’s (Aquaman, Game of Thrones) Duncan kneels before Paul, a moment in which the latter is officially recognised as the new Duke Atreides. These are all powerful scenes, each moving in its own way, each an illustration of just what Dune is capable of being when tackled properly.

But Villeneuve gives us the sort of stuff we’ve already seen, far too many times, in almost exactly the same iteration. It makes for boring viewing, really, to watch Oscar Isaac’s (Inside Llewyn Davis, Operation Finale) Duke Leto talk about wanting to be a force for good, unlike his Harkonnen predecessors. It’s almost as if Villeneuve is saying ‘Look, colonialism could have been a force for good if its practitioners were all top-notch folks’. Even Duncan gets to espouse the bravery of the native Fremen after he has gone ahead to Arrakis with an advance party and established contact with them. The sloppiness of trying to create a “good” imperialist power is for all to see, and it’s far too late in the day to say you’re adapting a 60s novel, just in case you’re going to try and make a break for it.

The only character with dimensions numbering more than one is Chalamet’s Paul. He is a bit of a brat, as one might expect an heir apparent to be, but he’s also skilled at Seer-like qualities his mother possesses and has inherited his father’s physical bravery (though none of Leto’s astuteness penetrates his progeny’s skull, nor his humility). The misstep is in how poorly Chalamet is directed: Villeneuve has him just be, which is fine because that is the character, only it gets one-note after a point, and Chalamet seems to struggle with having to keep a poker face for two-and-a-half hours. His scenes with Momoa are the best for this reason: because they allow the actor to break free of his director’s strange desire to have Paul be to Dune what Bella was to Twilight.

Running around in the background for much of the film is Half of Hollywood, the bigger names being Stellan Skarsgård (Good Will Hunting, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), Josh Brolin (Sicario – also a Villeneuve film and probably one of the best action films of the 21st century, Avengers: Infinity War), Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men, Skyfall), and Bautista (WWF/WWE, Spectre). Bardem is the standout, playing the Fremen leader Stillgar with equal amounts grace and fierceness, though he is saddled with another strange introduction scene that involves needless spitting. Villeneuve is unable to find a way to make the other parts significant enough, and even though Skarsgård is expectedly menacing as the antagonist Baron Harkonnen, he is given painfully little to do. Bautista and Brolin have it even worse, playing stock versions of the villain’s sidekick and the departed leader’s overzealous aide. Obviously, since Part Two will happen, these characters will be expanded, but Villeneuve seems to be totally disinterested in having the audience engage with them in any way, almost like he’s asking them to wait, and not in a good way.

That there is so much wrong with Dune hurts even more when you see the craft on display: Greig Fraser (Zero Dark Thirty, Lion) is a worthy successor to the rockstar that is Roger Deakins, inspiring awe and creating dread with his cinematography. Much of it is very formal, very symmetrical for the larger chunk of the film, and then, as the House Atreides falls, Fraser transitions to closer shots and chooses to forgo the use of tripods in favour of a shaky but coherent handheld style. The changeover in method makes Dune a million times more intimate, conveying to the audience a sense of the change in the film’s universe more efficiently than all the over-wrought writing (credited to Jon Spaihts – Doctor Strange, Passengers, Eric Roth – Forrest Gump, Munich, and Villeneuve).

There is also Patrick Vermette’s (Prisoners, Arrival) production design to admire, be it the haunting architecture or the monstrosities that the beings of Dune use for vehicles. It’s what really hurts the film, that so much of the world-building is so solid, so much of the artistry is jaw-dropping. Hell, Villeneuve himself outshines everyone when he’s showing off this great world he has transported from the page to the screen. He makes tremendous use of Hans Zimmer’s (The Lion King, Gladiator) soaring score, but the film is just sorely lacking a human touch, which is exactly what made Villeneuve’s Arrival such a stirring experience.

Dune has all the major moments you need in a film of its kind, but the inability to tap into a solitary emotion, even a negative one, is what keeps pulling it down even when it tries its darndest.

2 Comments