Oppenheimer

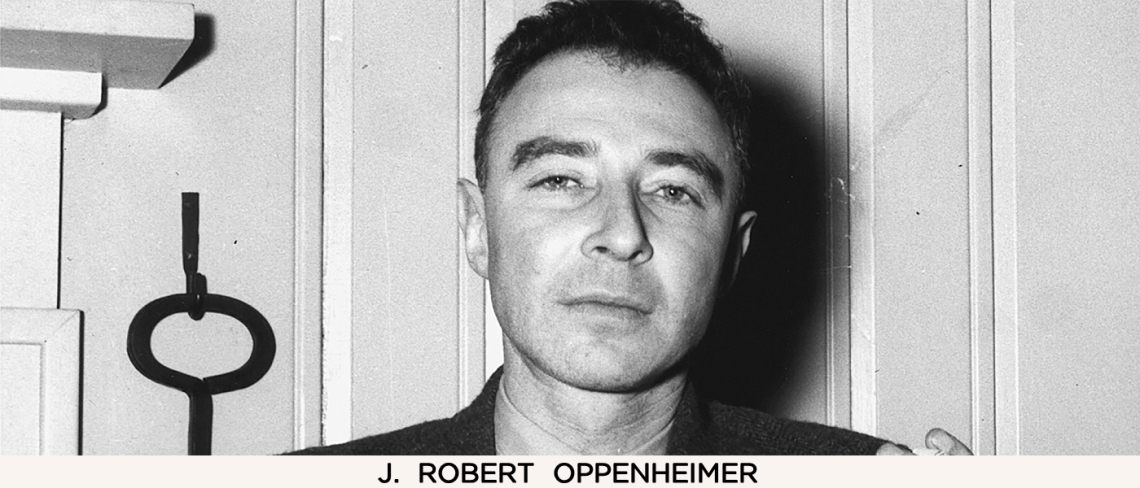

“He was America’s Prometheus, “the father of the atomic bomb,” who had led the effort to wrest from nature the awesome fire of the sun for his country in time of war.”

– “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, 2005.

On 16th December 2022, the US Secretary of Energy signed an order that went a small step in correcting a sixty-eight-year-old injustice: it vacated the 1954 order of a dissolved branch – the Atomic Energy Commission – “in the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer”. Justice, if one can call the decision that, was for one man alone: Oppenheimer’s son Peter, the sole living member of the family to have witnessed the machinations of the US government against his father.

The tragedy of Oppenheimer’s life – the ’54 hearing against the renewal of his security clearance, and its crowning triumph – the creation of the atomic bomb during World War II – come to life in Christopher Nolan’s twelfth feature film, an adaptation of the mammoth Pulitzer-winning American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. Nolan’s film is the kind that may well resuscitate a genre which is stylistically and thematically dead.

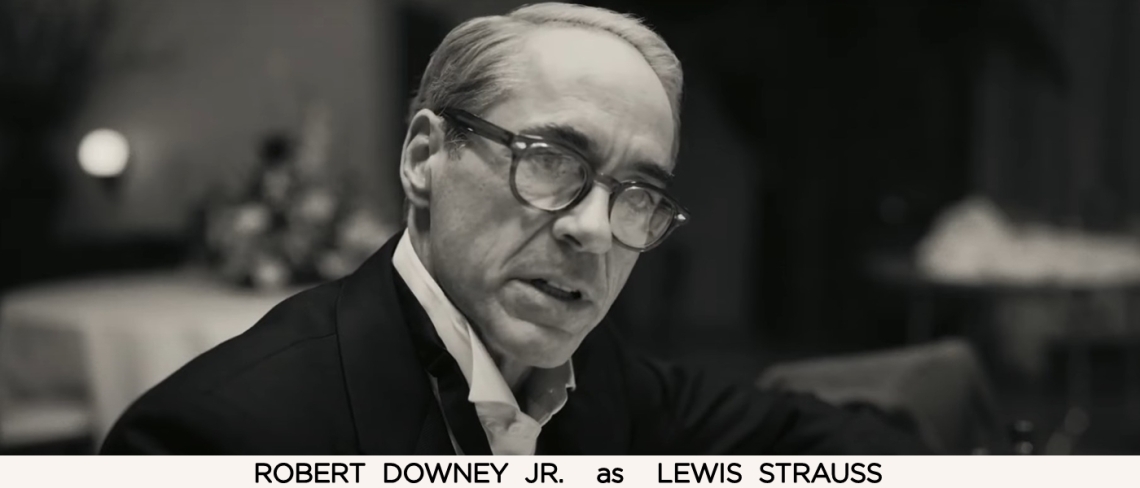

Nolan frames the film through two narratives: one is a largely linear, brusquely-cut account of Oppenheimer’s time at university through his teaching years, his directorship of the Los Alamos laboratory where the atomic bomb was brought to life, and then there is the track of his nemesis Lewis Strauss as he faces a Senate appointments committee on his way to serving as President Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce, through which Nolan draws out Oppenheimer’s fall from prominence.

The balance is tricky to find, especially because the film ventures into more avant-garde territory with its excursions into Oppenheimer’s psyche as events unfold, meshing his conflicts and conundrums with the hum-drum of going about the job of a quantum physicist. Nolan opts to interpret, through his special and visual effects departments, what went on in Oppenheimer’s mind, so atoms and molecules burst onto the screen, backed by Ludwig Görranson’s terrific score, and make the protagonist’s troubles appear as they are – muddled, over-wrought, complicated, and ultimately overwhelming. And in Cillian Murphy (Batman Begins, Peaky Blinders), Nolan finds a collaborator as malleable as can be.

Murphy’s interpretation of Oppenheimer is a curious exercise in externalising what is known of the man and internalising what went through his head. The more theatrical elements of it, the vanity of the man, for instance, is a performance by Oppenheimer that Murphy makes mincemeat of, and the charm he works up in sweeping off their feet Kitty Harrison (Emily Blunt) and Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) feels all too natural, but where Murphy really pulls out the stops is in relaying to the audience the hubris of the man in the run-up to Trinity, and his culpability in Hiroshima and Nagasaki which, it could be argued, is what led to Oppenheimer’s ousting from positions of policy-making. As the film flips back and forth, the duality of the man that Murphy brings to the crease keeps you hooked: his cockiness as the making of the bomb becomes central to his existence contrasts sharply with the haunted aura he has about him when the implications of nuclear armament make themselves clear. Easy as it is to toss around this sort of spiel, Murphy’s performance as Oppenheimer rivals the best work of his career so far – Damien O’Donovan in Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley, and that is a terrific turn.

Nolan and Murphy are supported by a tremendous supporting cast, headlined by Blunt, playing Oppenheimer’s fierce wife Kitty, and by Matt Damon, who plays Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, the Director of the Manhattan Project. Blunt has a handful of scenes but exudes a ferocity and a fragility that prove her the ideal foil for the sang-froid Oppenheimer maintains, and Damon is a delight as the tough-nut general who must assert his authority over dreamy scientists. It’s an odd marriage, the Groves-Oppenheimer pairing, and Damon-Murphy reinforce that in every interaction they have. As Oppenheimer’s on-off girlfriend, Pugh makes an impression, bringing a commanding presence to her handful of scenes. Oppenheimer is as populated a film as India is a country, but some of the actors leave a lasting impact: David Krumholtz (Isidor Isaac Rabi), Josh Hartnett (Ernest Lawrence), Benny Safdie (Edward Teller), and Jason Clarke (Roger Robb).

None, barring Murphy, naturally, matches up to Robert Downey Jr., who disappears into the role of Lewis Strauss (that’s pronounced Straws, mind you!). Downey, who has spent much of the last decade and a half playing a slightly exaggerated version of himself, is a force to be reckoned with, much like the man he plays. What Downey and Nolan do with the ambitious, vindictive businessman is make him compelling through empathy: the film spends a fair bit of time with Strauss, and Downey plays him with a measure of ambition, general decency, but also with a streak of nastiness that seldom rises to the surface. Downey convinces you that Strauss’ actions wound their way to an almost natural conclusion, that what happened to Oppenheimer was destined to be. That it was not, that it was the machinations of a wounded man and an anti-Left establishment are what the film and Downey eventually make clear.

Over the years, if there is a piece of criticism that has stuck to Nolan, it is that his films, while conceptually interesting, often find themselves hobbled by the screenplays he delivers. While I don’t quite agree with that (Dunkirk is a terrific screenplay), there is some truth to the discourse, most accurately when it comes to his exposition. Well, there’s news for the worried folks – this is Nolan’s best-written film, and the dialogue is a whizz-banger, almost out of the Aaron Sorkin ratatat playbook. The transitions and back-and-forth are aided by Jennifer Lame’s excellent editing, of course, but the writing packs a punch in keeping you hooked. Lame, for her part, makes the narrative’s episodic structure work with some deft cutting that makes the film feels like a jaunt which, at three hours, it obviously is not. And lest the mind wanders (not that Nolan allows that to happen), there’s Hoyte van Hoytema’s jaw-dropping photography to admire. For a film which is a third in black-and-white, the parts of Oppenheimer that play out in colour are some of Nolan’s most vivid pictures, and Hoytema’s camera, which freewheeled over the Channel in Dunkirk, has a similar rhythm to it in scoping out the desert of New Mexico. The focus on close-ups plays into the sense of the film being at least partially a psychological drama, and the grand vistas give it an epic scale. In that sense, the Nolan-Hoytema combine comes eerily close to some of the work David Lean and Freddie Young did on Lawrence of Arabia, and I have not even considered thematic similarity.

Oppenheimer is an experience that is increasingly rare in a cinema landscape that tilts towards larger audiences and franchise-able “content”. It is an achievement then, both for its time and otherwise. In a more straightforward way, it is cinema as we have known it longest, the kind we go to not for end-credits sequences and which doesn’t require an audience member to watch a plethora of things beforehand. And in the trigger-happy times we live in, Nolan chooses to run with the life of a man that makes you wonder, to quote Bird and Sherwin: “Can criticism of a government’s policies be equated with disloyalty to country?”

For better or for worse, J. Robert Oppenheimer altered the realm of human reality forever – the world we inhabit today is a bequest from him (among others); in a much smaller way, Christopher Nolan’s engagement with cinema has forever altered our relationship with the art form, and dare I say it’s a privilege to be watching films as he’s making them.

Very nicely written. !! Varry Axcallant !!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person